The O.L.I.O (Osservatorio Laboratorio Internazionale Olio Evo) FORUM, at the Veronafiere Auditorium, aimed to get a structured and proactive reflection started in Verona to relaunch the olive oil sector and build a shared planning process that would focus on the needs and problems of producers and exporters.

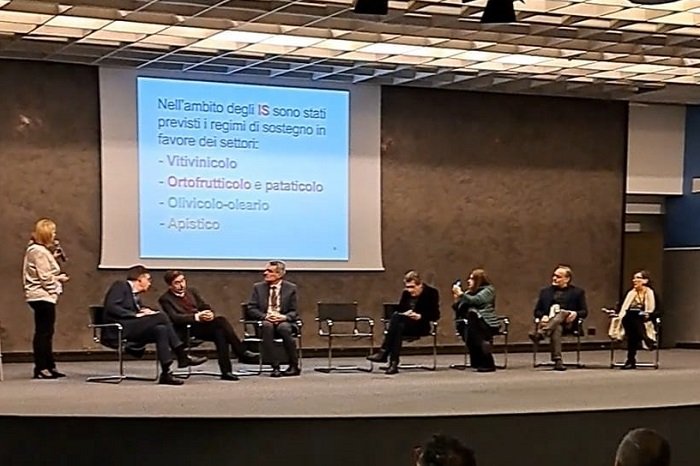

The first part of the event featured Veronica Bertoldo (Veneto Region), Enzo Gambin (Aipo director), Marco Oreggia (Flos Olei publisher and journalist), Professor Diego Begalli (University of Verona), Professor Nicola Mori (University of Verona), and journalists Luigi Cremona and Lorenza Vitali.

They discussed the production crisis and rising costs, but also climate change and new ways to revive communication of a product of excellence in Italian agricultural culture.

The oil sector, which relies on the work of so many small businesses, is a system that contributes enormous value, but whose fragmented production structure risks losing so many opportunities for growth and thus investment.

Space is also given to a reflection on the EU’s new 2023/2027 CAP with rules to support National Strategic Plans and an analysis of producer organizations (POs) aimed at promoting cooperation among farmers.

“Oil started to be talked about when prices went up,” explained Enzo Gambin (Aipo). In Italy there is an olive and olive oil business that has special characteristics, just think of the more than 500 varieties of olive trees and the very many PDO and PGI products. Olive oil should be a high-speed train, but instead it is a train that goes too slow. Within the world of Italian olive growing there is little inclination for change.”

In Italy small businesses

The data speak for themselves: 70 percent of Italian olive growing is governed by small farms that hardly reach 2 hectares, with 180-200 trees, and throughout Italy we now do not reach 300 thousand tons of oil produced. Numbers that are causing us to slide down in the ranking of oil producers, with Spain and Morocco leading the way.

To regain high production potential, investment must be made in research, research geared toward optimizing resources and more and faster field service.

“There is little oil in Italy, and we buy it everywhere in order to saturate a market that now demands more than we can give,” explains Marco Oreggia (Flos Olei). If there really is a will to change pace, downward policy is not needed. We need to recover forgotten varieties and focus on marketing, we are 20 years behind, we are also in an emergency in terms of climate problems and diseases. In other non-EU countries they are already getting their act together and on the shelves there is no extra virgin, only virgin olive; in Brazil they had the courage to do this to boost the olive economy. We can either change our perspective or play along with Spain, which dictates the rules and whose production crisis has cascaded into higher prices.”

Economic revitalization is needed

The revitalization of the product was then also discussed from an economic perspective, and Prof. Begalli focused his analysis on the importance of “passing on the value and not just the price of a product.” Oil needs to be communicated in a certain way to justify its cost, its benefits, health content and even all the thinking about nutraceuticals that is not yet valued enough needs to be brought to the consumer’s attention, which is why “an umbrella brand would be needed to convey these messages and present strong product lines to the market, particularly the international market,” the professor stresses.

In the area of climate change, the focus fell on phytosanitary treatments, as Prof. Mori explained, “If olive fly used to be a problem in southern regions now it is moving north. We no longer have harsh winters, so there are no longer limiting temperatures for this phytophage. Then in the north also came the Asian bug, which was not present in our areas, but now it has adapted to our climate causing major limitations.”

Agriculture 4.0

Technology, however, can come to help; in fact, systems are being studied that take advantage of drones, for example, to distribute plant protection products, so as to reduce their use and have more targeted action. Then there are the remotely controlled electronic traps with artificial intelligence that are trained to recognize and stop insects. And then again small Rovers traverse the field and are able to monitor the health of the plants. It is a form of Agriculture 4.0 that allows real-time actions to be triggered to counter any problems or difficulties the plant is experiencing.

Technology, however, can come to help; in fact, systems are being studied that take advantage of drones, for example, to distribute plant protection products, so as to reduce their use and have more targeted action. Then there are the remotely controlled electronic traps with artificial intelligence that are trained to recognize and stop insects. And then again small Rovers traverse the field and are able to monitor the health of the plants. It is a form of Agriculture 4.0 that allows real-time actions to be triggered to counter any problems or difficulties the plant is experiencing.

And while growing olive trees is becoming increasingly difficult, its knowledge by the general public remains limited, and only in recent years has the culture of olive oil grown, thanks in part to catering. “Oil gives so much value to dishes, for many chefs it has become a real signature, the closing of the dish, a refined touch. That’s why it must be told, made to be appreciated and then enjoyed,” explains journalist Luigi Cremona.

“Olea Mundi” the world’s collection of olive trees.

Then they talked about the virtuous case of the municipality of Lugnano in Teverina (Terni), which since 2014 has been home to “Olea Mundi,” the world’s collection of olive trees, some 1,200 plants from as many as 23 olive-growing countries in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and new growing areas. An example of a small territory that has rebuilt itself on oil culture. Thus literary prizes, events and projects with schools were born to put the land and its liquid gold back at the center.

International experiences

In the second part dedicated first to international experiences and then to a round table discussion, coordinated by Radio 24 journalist Rosanna Magnano, Marko Markovic (Istria Tourist Board) Duccio Morozzo (Director Olive Bureau srl), Alessandra di Canossa (Soc. Agr. Guidalberto di Canossa), Gianfranco Comincioli (Az. Agr. Comincioli), Massimiliano Consolo (Business Developer Mark Up), Giancarlo Bonamini (Frantoio Bonamini) and Giovanni di Mambro (co-founder of Elaisian) spoke. Space for a reflection onoleotourism with the case study of Istria, which has set up a series of activities to boost tourism combined with the world of oil.

To revive oil, “we need to value not only the product, but also the territory, it must be a pride to value our own cultivars,” Morozzo explains. Italian producers then need to stop entrenching themselves in their own positions and thinking that they are the best, the new countries started from our achievements and are now surpassing us thanks to and technology and skills. It is time to challenge ourselves.”

The topic of generational transition was also discussed , a difficult topic because work is not always able to be passed on from father to son, with the risk of centuries-long traditions being lost. “Young people who decide to take up the challenge and have the opportunity to travel and study then return home full of ideas and solutions to address problems,” di Mambro explains.

“The basic problem is that there is no product and no labor,” Comincioli strongly emphasizes. Let’s go back to manufacturing and take advantage, when needed, of technology to develop new solutions compatible with the territory. We’ve been talking about the same problems for decades; it’s really time for a change.”

The event was promoted by Aipo (Interregional Olive Producers Association), Frantoio Bonamini, Flos Olei, Innovaa, Innosap, InnovatiVE and Terzomillennium with the sponsorship of the Province of Verona, the Veneto Regional Council and the University of Verona and the technical sponsorship of Veronafiere-SOL and Banco Desio.